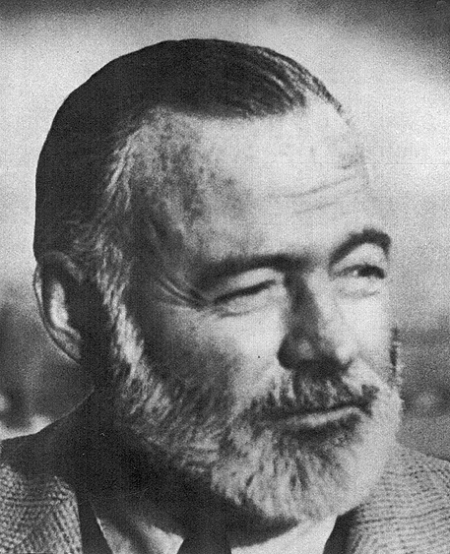

& After dinner that night we tuned to PBS. It had been a fine documentary from a fine documentarian. So far, it had been fine. We expected more from the concluding installment and got it. Ken Burns had sparred and hit hard for two nights against the myth of Papa. By the third night the myth still stood. But its legs had gone. You could tell.

She settled into the flowered divan and touched her lips to the rim of the cup of decaf and recoiled from its steam. “Will he keep pounding, do you expect?” She put the cup in the saucer on the coffee table and curled her legs under her skirt. “Burns, I mean?”

“Yes. Heavyweights can have no mercy. Burns is a heavy. It’s time.”

The pounding went through the final two hours, Peter Coyote’s monotone narrative needing no support from adjectives. It was Hem’s story with no frills, told as he might have told it, but never could have. The truth hurt. That night’s installment, told by Papa, would have been self-abuse. His creed was to abuse only others. That night, jabs came from Burns with increasing authority and grew into gut-whuffing punches and the knees rubbered and sprays of sweat exploded from the brow with each unerring thudding hook to the jaw. They were honest hooks and efficient. They came one and another. They came from former and current wives and writers and critics and even a son with force and sincerity and no pity. It was brutal and it was time.

The old inventor of a new literature had written some good books and some stinkers, working hard on the words and harder on exaggerating his exploits and his virility and denying his self-doubts that drew him again and again to brushes with death, watching, from ringside, mostly, as Spanish bulls and battalions of soldiers died. He had memorialized them and won prizes – Pulitzer and Nobel — and lost the love of four wives and two sons and had never quit drinking. He had resurrected his unravelling status with his last novel – perhaps the greatest story he ever told – and then, like the once gallant bull must finally assent to the pain of the picas and the deep slice of the matador’s sword, he sat down in his slippers and rested his forehead on the business end of a shotgun barrel.

And then he pulled the trigger. His fourth wife, Mary, who had once told him “you have not been the good man you said you intended to be [and] insulted me and my dignity as a human being” heard the gun go off. She could not have been surprised. He had talked about, threatened, played at the edges of suicide many times. She may have not been prepared for his splattered remains, his final insult to her dignity.

Afterwards, we put on our coats and went out. We were quiet for awhile and walked until it started to drizzle. “That must have been a real mess he left her,” she said from deep in her hoodie. “He really was a son of a bitch.”

“Yes. And a helluva writer.”

And then we walked back to the house in the rain.

& Enlightened about one for whom the bell tolled, I’m outta here.